What if saving one life could doom millions?

In Stephen King’s 11/22/63, a man named Jake discovers a portal that transports him back to 1958. Determined to prevent the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, he believes this single act will benefit humanity. After years of meticulous planning, he succeeds in altering history. But when he returns to the present, he finds a world ravaged by earthquakes and nuclear war—a dystopian reality far worse than the one he left behind. Devastated, Jake goes back once more to reset the timeline.

This gripping tale illustrates a profound truth: small changes can trigger vast and unpredictable outcomes in complex systems. This phenomenon is known as the butterfly effect—the idea that tiny actions can have non-linear impacts on a global scale.

Rather than imagining a butterfly causing a typhoon, consider how a minor software glitch can cascade into a massive system failure, affecting millions. In our interconnected world, initial conditions are everything. As John Gribbin writes in Deep Simplicity, “Some systems are very sensitive to their starting conditions, so that a tiny difference in the initial ‘push’ you give them causes a big difference in where they end up, and there is feedback, so that what a system does affects its own behavior.”

Understanding the butterfly effect offers a new lens through which to view business, markets, and life itself. It reminds us that every action, no matter how small, can set off a chain of events we might never foresee. So the next time you make a decision, remember: you could be unleashing consequences far beyond your imagination.

You could not remove a single grain of sand from its place without thereby … changing something throughout all parts of the immeasurable whole.

Fichte, The Vocation of Man (1800)

What the Butterfly Effect Is Not

The point of the butterfly effect is not to gain leverage. As General Stanley McChrystal writes in Team of Teams:

In popular culture, the term “butterfly effect” is almost always misused. It has become synonymous with “leverage”—the idea of a small thing that has a big impact, with the implication that, like a lever, it can be manipulated to a desired end. This misses the point of Lorenz’s insight. The reality is that small things in a complex system may have no effect or a massive one, and it is virtually impossible to know which will turn out to be the case.

Benjamin Franklin offered a poetic perspective in his variation of a proverb that’s been around since the 14th century in English and the 13th century in German, long before the identification of the butterfly effect:

For want of a nail the shoe was lost,

For want of a shoe the horse was lost,

For want of a horse the rider was lost,

For want of a rider the battle was lost,

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost,

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

The lack of one horseshoe nail could be inconsequential, or it could indirectly cause the loss of a war. There is no way to predict which outcome will occur. (If you want an excellent book to teach this idea to your children, check out If You Give a Mouse a Cookie.)

In this post, we will seek to unravel the butterfly effect from its many incorrect connotations and build an understanding of how it affects our individual lives and the world in general.

Edward Lorenz and the Discovery of the Butterfly Effect

It used to be thought that the events that changed the world were things like big bombs, maniac politicians, huge earthquakes, or vast population movements, but it has now been realized that this is a very old-fashioned view held by people totally out of touch with modern thought. The things that change the world, according to Chaos theory, are the tiny things. A butterfly flaps its wings in the Amazonian jungle, and subsequently a storm ravages half of Europe.

Good Omens, by Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman

Although the concept of the butterfly effect has long been debated, the identification of it as a distinct effect is credited to Edward Lorenz (1917–2008).

Lorenz was a meteorologist and mathematician who combined the two disciplines to create chaos theory. During the 1950s, he searched for a means of predicting the weather, as he found linear models ineffective.

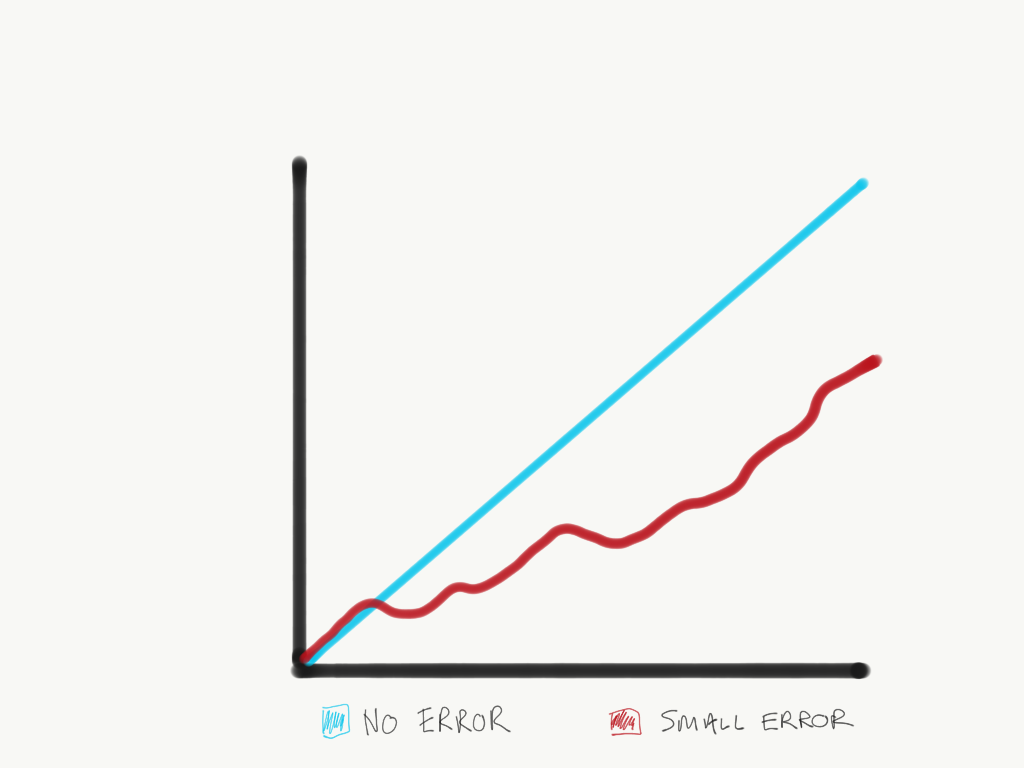

In an experiment to model a weather prediction, he entered the initial condition as 0.506, instead of 0.506127. The result was surprising: a very different prediction. From this, he deduced that the weather must turn on a dime. A tiny change in the initial conditions had enormous long-term implications.

By 1963, he had formulated his ideas enough to publish an award-winning paper entitled Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow. In it, Lorenz theorized that weather prediction models are inaccurate because knowing the precise starting conditions is impossible, and a tiny change can throw off the results. Lorenz began to use the butterfly analogy to make the concept understandable to non-scientific audiences.

Lorenz explained that a butterfly’s wing flap represents tiny atmospheric changes. These don’t create typhoons but can alter their paths. As these small changes compound in complex systems, they can have massive implications. Lorenz concluded this makes weather prediction impossible. He wrote:

If, then, there is any error whatever in observing the present state—and in any real system such errors seem inevitable—an acceptable prediction of an instantaneous state in the distant future may well be impossible.

… In view of the inevitable inaccuracy and incompleteness of weather observations, precise very-long-range forecasting would seem to be nonexistent.

Lorenz emphasized that we can’t pinpoint what exactly tips a system. The butterfly symbolizes this unknowable factor.

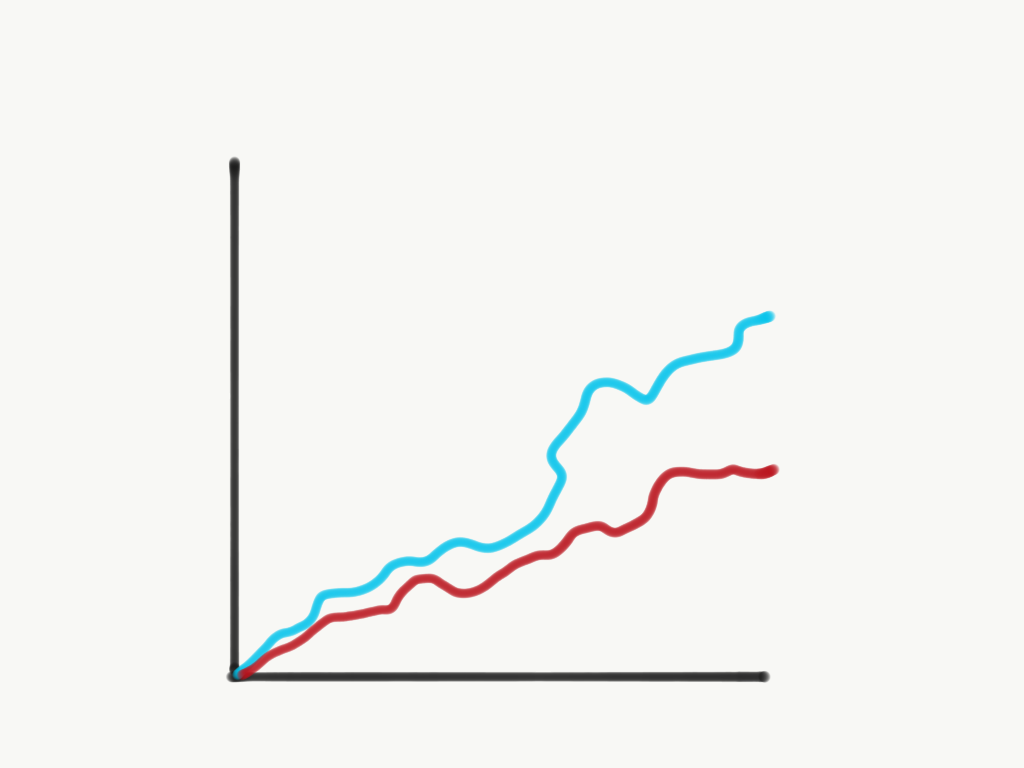

He challenged predictive models assuming linear, deterministic progression. Even tiny initial errors render these models useless as inaccuracies compound over time. This exponential growth of errors, known as deterministic chaos, occurs in most systems, simple or complex.

The butterfly effect is humbling. It exposes flaws in other models, showing science to be less accurate than we assume. We can’t make precise predictions due to exponential error growth.

Before Lorenz, people thought approximate initial conditions would yield approximate outcomes. In Chaos: Making a New Science, James Gleick writes:

The models would churn through complicated, somewhat arbitrary webs of equations, meant to turn measurements of initial conditions … into a simulation of future trends. The programmers hoped the results were not too grossly distorted by the many unavoidable simplifying assumptions. If a model did anything too bizarre … the programmers would revise the equations to bring the output back in line with expectation… Models proved dismally blind to what the future would bring, but many people who should have known better acted as though they believed the results.

One theoretician declared, “The basic idea of Western science is that you don’t have to take into account the falling of a leaf on some planet in another galaxy when you’re trying to account for the motion of a billiard ball on a pool table on earth.”

Lorenz’s work was revolutionary. It proved that without perfect knowledge of initial conditions, predictions are useless—a shocking revelation.

Early computer enthusiasts believed machines would unlock complex systems, enabling accurate predictions. After millennia of being weather’s slaves, humans craved control. Lorenz’s innocent discovery shattered this dream, sending ripples far beyond meteorology.

Ray Bradbury, the Butterfly Effect, and the Arrow of Time

Ray Bradbury’s A Sound of Thunder predates chaos theory and the butterfly effect. Set in 2055, it follows Eckels, who time-travels 65 million years to hunt a dinosaur. Despite warnings, he steps off the path during the hunt, panicked by a T. Rex. Upon return to 2055, they find the world altered: language has changed, and a dictator rules. Eckels discovers a crushed butterfly on his boot, realizing his misstep changed the future. Bradbury writes:

Eckels felt himself fall into a chair. He fumbled crazily at the thick slime on his boots. He held up a clod of dirt, trembling, “No, it cannot be. Not a little thing like that. No!”

Embedded in the mud, glistening green and gold and black, was a butterfly, very beautiful and very dead.

“Not a little thing like that! Not a butterfly!” cried Eckels.

It fell to the floor, an exquisite thing, a small thing that could upset balances and knock down a line of small dominoes and then big dominoes and then gigantic dominoes, all down the years across Time. Eckels’ mind whirled. It couldn’t change things. Killing one butterfly couldn’t be that important! Could it?

Bradbury envisioned the passage of time as fragile and liable to be disturbed by minor changes.

Since A Sound of Thunder’s publication, physicists have debated its accuracy. While time travel remains impossible, the story raises questions about time’s nature and determinism.

Physicists discuss the Arrow of Time—entropy’s irreversible progression. As time advances, matter becomes more chaotic, never spontaneously reverting to its original state. A broken egg stays broken. This gives us our sense of past, present, and future.

Let us draw an arrow arbitrarily. If as we follow the arrow we find more and more of the random element in the state of the world, then the arrow is pointing towards the future; if the random element decreases the arrow points towards the past. That is the only distinction known to physics. This follows at once if our fundamental contention is admitted that the introduction of randomness is the only thing which cannot be undone.

Time, as we perceive it, exists due to entropy. If entropy is irreversible, time exists. Our best measure of time is entropy. If time is a journey towards chaos, small changes could indeed amplify that chaos, affecting the future.

We’re unsure if entropy creates time or vice versa. Thus, we can’t know if changing the past would alter the future. Would a crushed butterfly really shift entropy’s path? Was Eckels’ misstep free will or predestined? Was the dictatorial future inevitable?

These ideas—butterfly effect, chaos theory, determinism, free will, and time travel—have inspired many imaginations and resulted in films ranging from It’s a Wonderful Life to Donnie Darko. However, fiction often portrays the butterfly as a direct cause. Lorenz’s original concept emphasizes that small, unidentifiable details can tip the balance.

The Butterfly Effect in Business

In business, the butterfly effect means that tiny decisions or actions can snowball into major outcomes.

Imagine you’re starting a lemonade stand. You decide to smile at your first customer. That’s a small thing, right? But that customer tells their friends how friendly you were. Those friends come buy lemonade too. One of them happens to be the mayor’s kid. The mayor hears about your stand and mentions it in a speech. Suddenly, you’ve got lines around the block.

All from that first smile.

But it works the other way too. Maybe you’re grumpy to that first customer. They tell their friends to avoid your stand. Business dries up before it even starts.

The key is, you often can’t predict which small action will lead to big changes. That’s why in business, every detail matters. How you treat each customer, how you write each email, how you design your product – it could all have outsized effects. (Read more in The Physics of Relationships)

This isn’t just true for small businesses. Look at big tech companies. Facebook started as a way for college students to connect. Nobody could have predicted it would change global politics. But small decisions early on – like expanding to more colleges, or adding the News Feed – set off chain reactions that led to huge consequences.

The butterfly effect teaches us two important lessons for business:

- Pay attention to details. Small things matter more than you think.

- Be adaptable. Since you can’t predict everything, you need to be ready to adjust when those small changes start causing big effects.

Remember, in business, as in life, there’s no such thing as a small decision. Everything you do could be the butterfly’s wings that start a hurricane.

The Butterfly Effect in Economics

The global economy can be considered a single system. Much like a giant game of dominoes, one small change can set off a chain reaction that affects everyone.

Benoit Mandelbrot began applying the butterfly effect to economics several decades ago. In a 1999 article for Scientific American, he explained his findings. Mandelbrot saw how unstable markets could be, and he cited an example of a company that saw its stock drop 40% in one day, followed by another 6%, before rising by 10%—the typhoon created by an unseen butterfly.

When Benoit looked at traditional economic models, he found that they did not even allow for such events. Standard models denied the existence of dramatic market shifts. In Scientific American, he wrote:

According to portfolio theory, the probability of these large fluctuations would be a few millionths of a millionth of a millionth of a millionth. (The fluctuations are greater than 10 standard deviations.) But in fact, one observes spikes on a regular basis—as often as every month—and their probability amounts to a few hundredths.

If these changes are unpredictable, what causes them?

Mandelbrot’s answer lay in his work on fractals. A simple definition of fractals comes from Mandelbrot himself: “A fractal is a geometric shape that can be separated into parts, each of which is a reduced-scale version of the whole.” Going on to explain the connection, he writes:

In finance, this concept is not a rootless abstraction but a theoretical reformulation of a down-to-earth bit of market folklore—namely that movements of a stock or currency all look alike when a market chart is enlarged or reduced so that it fits the same time and price scale. An observer then cannot tell which of the data concern prices that change from week to week, day to day or hour to hour. This quality defines the charts as fractal curves and makes available many powerful tools of mathematical and computer analysis.”

In a talk, Mandelbrot held up his coffee and declared that predicting its temperature in a minute is impossible, but in an hour is perfectly possible. The same concept applies to markets. Even if a long-term pattern can be deduced, it is of little use to those who trade on a shorter timescale.

Mandelbrot explains how his fractals can be used to create a more useful model of the chaotic nature of the economy:

Instead, multifractals can be put to work to “stress-test” a portfolio. In this technique, the rules underlying multifractals attempt to create the same patterns of variability as do the unknown rules that govern actual markets. Multifractals describe accurately the relation between the shape of the generator and the patterns of up-and-down swings of prices to be found on charts of real market data… They provide estimates of the probability of what the market might do and allow one to prepare for inevitable sea changes. The new modeling techniques are designed to cast a light of order into the seemingly impenetrable thicket of the financial markets. They also recognize the mariner’s warning that, as recent events demonstrate, deserves to be heeded: On even the calmest sea, a gale may be just over the horizon.

In The Misbehaviour of Markets, Mandelbrot and Richard Hudson expand on financial chaos. They begin with a discussion of the infamous 2008 crash and its implications:

The worldwide market crash of autumn 2008 had many causes: greedy bankers, lax regulators and gullible investors, to name a few. But there is also a less-obvious cause: our all-too-limited understanding of how markets work, how prices move and how risks evolve. …

Markets are complex, and treacherous. The bone-chilling fall of September 29, 2008—a 7 percent, 777 point plunge in the Dow Jones Industrial Average—was, in historical terms, just a particularly dramatic demonstration of that fact. In just a few hours, more than $1.6 trillion was wiped off the value of American industry—$5 trillion worldwide.

Mandelbrot and Hudson argue that the 2008 crisis partly stemmed from overconfidence in financial predictions. Model creators ignored the butterfly effect: no model, however complex, can perfectly capture initial conditions or compound effects of small changes.

Before Lorenz’s work, people thought they could predict and control the weather. Similarly, they believe they could do this with markets until some unexpected event proves otherwise. Wall Street banks, trusting their models, felt safe borrowing huge sums for what was essentially gambling (without knowing they were gambling). Their models said a crash was impossible. It happened anyway. While we learn from our mistakes and think we’ve finally figured it out this time, we are eventually proven wrong. All models are false.

Mandelbrot and Hudson note that predictive models treat markets as “risky but ultimately… manageable.” Like weather forecasts, economic predictions use approximate initial conditions—which we now know are nearly useless. They write:

[C]auses are usually obscure. … The precise market mechanism that links news to price, cause to effect, is mysterious and seems inconsistent. Threat of war: Dollar falls. Threat of war: Dollar rises. Which of the two will actually happen? After the fact, it seems obvious; in hindsight, fundamental analysis can be reconstituted and is always brilliant. But before the fact, both outcomes may seem equally likely.

In the same way that apparently similar weather conditions can create drastically different outcomes, apparently similar market conditions can create drastically different outcomes.

We cannot see the extent to which the economy is interconnected, and we cannot identify where the butterfly lies. Mandelbrot and Hudson disagree with the view of the economy as separate from other parts of our world. Everything connects:

No one is alone in this world. No act is without consequences for others. It is a tenet of chaos theory that, in dynamical systems, the outcome of any process is sensitive to its starting point—or in the famous cliché, the flap of a butterfly’s wings in the Amazon can cause a tornado in Texas. I do not assert that markets are chaotic…. But clearly, the global economy is an unfathomably complicated machine. To all the complexity of the physical world… you add the psychological complexity of men acting on their fleeting expectations….

Why do people prefer to blame crashes (such as the 2008 credit crisis) on the folly of those in the financial industry? Jonathan Cainer provides a succinct explanation:

Why do we love the idea that people might be secretly working together to control and organize the world? Because we do not like to face the fact that our world runs on a combination of chaos, incompetence, and confusion.

Historic Examples of the Butterfly Effect

“

A very small cause which escapes our notice determines a considerable effect that we cannot fail to see, and then we say the effect is due to chance. If we knew exactly the laws of nature and the situation of the universe at the initial moment, we could predict exactly the situation of that same universe at a succeeding moment. But even if it were the case that the natural laws had no longer any secret for us, we could still only know the initial situation approximately. If that enabled us to predict the succeeding situation with the same approximation, that is all we require, and we should say that the phenomenon had been predicted, that it is governed by laws. But it is not always so; it may happen that small differences in the initial conditions produce very great ones in the final phenomena. A small error in the former will produce an enormous error in the latter. Prediction becomes impossible, and we have the fortuitous phenomenon.

Jules Henri Poincaré (1854–1912)

The butterfly effect shows how tiny details can lead to massive changes. Here are a few examples:

- The bombing of Nagasaki: Cloud cover over the original target, Kuroko, led to Nagasaki being bombed instead. A simple weather change altered history.

- Hitler’s art school rejection: Twice rejected from art school at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, Hitler’s path changed from aspiring artist to dictator. Imagine if he’d been accepted.

- Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination: A wrong turn by his driver put him in the path of his assassin. This sparked World War I.

- The Chernobyl disaster: Three workers prevented a second explosion that could have made half of Europe uninhabitable. Their actions limited the catastrophe.

- The Cuban Missile Crisis: One Russian officer, Vasili Arkhipov, vetoed launching a nuclear torpedo. He likely prevented World War III.

These examples show how fragile our world is. Small events can have enormous consequences.

We often think we can predict and control complex systems like weather or the economy. The butterfly effect proves we can’t. These systems are chaotic and can change suddenly.

At best, we can try to create good starting conditions and be aware of potential catalysts. But we can’t control or predict outcomes perfectly. Thinking we can only sets us up for failure.