We all know one, the Monday morning quarterback.

They walk into the meeting room primed and ready for action. Ready that is, to apply the knowledge they know now to decisions of the past. And too often we’re defenseless.

The outcome by now is likely apparent to everyone.

“When a decision goes awry,” writes Albert Bernstein in his book Dinosaur Brains, “we tend to focus on the people who made it, rather than on the decision itself. Our assumption, which is really unwarranted, is that good people make good decisions, and vice versa.”

The point is to focus on what was known at the time. And consider, in light of that, was it a reasonable decision?

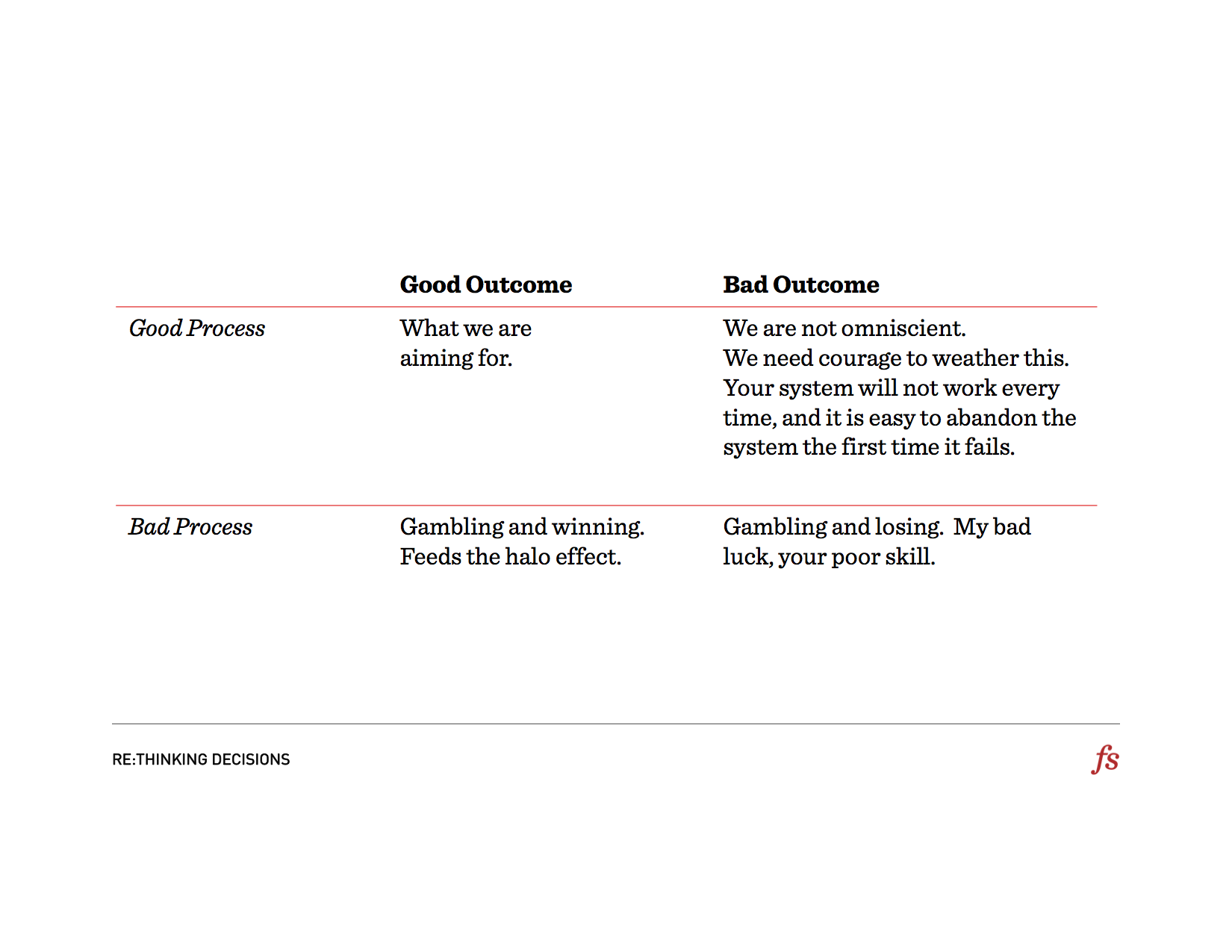

Good decisions don’t always have a good outcome, just as bad decisions don’t always have bad outcomes. It’s scary but a lot of otherwise smart people are unable to distinguish the difference.

This image from our rethink conference on decision making helps us understand what’s going on.

It’s easy to shine the spotlight on the outcome. It doesn’t involve a lot of thinking either and it certainly isn’t going to help you understand or diagnose problems.

It’s harder, yet profitable, to think back and evaluate the merits of a particular decision based on what was known at the time. Was it a good decision with a bad outcome?

But usually, the only information we have about how and why decisions were made is the self-serving memories of the people in the room. “We have very little vocabulary for talking about internal thought processes,” writes James March, “Decisions feel as if they jump fully grown from one’s head.”

This is where having a good decisionprocess comes in. Keeping a decision journals is also helpful.

Maybe executives in responsible positions should be required to keep logs, as sea captains do. After each decision, a manager would list his or her reasons for having made it and record how it turned out.

If you have a journal, you can pull it out and see, in light of the facts and assumptions at the time, whether the best decision possible was made and if there was, in fact, a mistake.

If there really was a mistake, you can look at your decision process and determine what went wrong and how to avoid it in the future. Don’t hide mistakes behind vagueness but, equally important, stay away from the blame/credit mentality because it undermines understanding. And understanding is the key to getting better.

One way to reinforce good decisions is to document the assumptions at the time the decision is made in a decision journal.

Read the ultimate guide to making smart decisions next.