Great decisions come from understanding where you have an advantage.

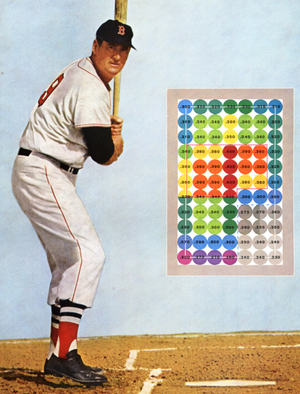

Ted Williams, baseball’s last .400 hitter, demonstrated this principle through a remarkably systematic approach to hitting.

Williams divided the strike zone into 77 squares, mapping his success rate for each area. This detailed self-knowledge revealed a crucial insight: when he waited for pitches in his sweet spot, he hit .400; when he swung at marginal pitches, his average dropped to .230-.250.

Put differently, when he was patient and waited for the right pitch, he hit better than when he was impatient and needed to swing. Simple but not easy.

Waiting for the right pitch is simple but not easy.

This principle extends far beyond baseball. Top performers in any field succeed by:

- Identifying their circle of competence – areas where they have genuine expertise

- Recognizing the boundaries of that expertise

- Patiently waiting for opportunities within their sweet spot

Warren Buffett exemplifies this approach in investing. He writes: “If we have a strength, it is in recognizing when we are well within our cycle of competence and when we are approaching the perimeter.”

Like Williams, Buffett waits for the perfect pitch, reviewing thousands of investments to find ones squarely within his expertise.

Unlike Williams, Buffett can’t be called “out” on strikes if he resists pitches that are barely in the strike zone. He can, quite literally, wait for the perfect pitch—looking at thousands of different investments before finding one that is just right.

Most of us, however, simply can’t wait forever. Sometimes, we’re forced to make a decision. Interestingly, there is a parallel with hitting again.

Consider this excerpt from Clear Thinking: Turning Ordinary Moments into Extraordinary Results:

“You don’t need to be smarter than others to outperform them if you can out-position them. Anyone looks like a genius when they’re in a good position, and even the smartest person looks like an idiot when they’re in a bad one.

Sounds like Williams, who understood that average batters could become great if they waited for the right pitch, and even the best could become average if they swung at the wrong pitch.

A good hitter can hit a pitch that is over the plate three times better than a great hitter with a questionable ball in a tough spot.

Two key strategies for operating outside your circle of competence:

- Focus on positioning rather than prediction

- Build in a margin of safety to account for uncertainty

Success comes not from expanding your circle of competence endlessly but from:

- Clearly mapping its boundaries

- Operating primarily within it

- Take careful, protected steps when venturing beyond it.