We all try to avoid uncertainty, even if it means being wrong. We take comfort in certainty, and we demand it of others, even when we know it’s impossible.

Gerd Gigerenzer argues in Risk Savvy: How to Make Good Decisions that life would be pretty dull without uncertainty.

If we knew everything about the future with certainty, our lives would be drained of emotion. No surprise and pleasure, no joy or thrill— we knew it all along. The first kiss, the first proposal, the birth of a healthy child would be about as exciting as last year’s weather report. If our world ever turned certain, life would be mind-numbingly dull.

The Illusion of Certainty

We demand certainty of others. We ask our bankers, doctors, and political leaders (among others) to give it to us. What they deliver, however, is the illusion of certainty. We feel comfortable with this.

Many of us smile at old-fashioned fortune-tellers. But when the soothsayers work with computer algorithms rather than tarot cards, we take their predictions seriously and are prepared to pay for them. The most astounding part is our collective amnesia: Most of us are still anxious to see stock market predictions even if they have been consistently wrong year after year.

Technology changes how we see things – it amplifies the illusion of certainty.

When an astrologer calculates an expert horoscope for you and foretells that you will develop a serious illness and might even die at age forty-nine, will you tremble when the date approaches? Some 4 percent of Germans would; they believe that an expert horoscope is absolutely certain.

…

But when technology is involved, the illusion of certainty is amplified. Forty-four percent of people surveyed think that the result of a screening mammogram is certain. In fact, mammograms fail to detect about ten percent of cancers, and the younger the women being tested, the more error-prone the results, because their breasts are denser.

“Not understanding a new technology is one thing,” Gigerenzer writes, “believing that it delivers certainty is another.”

It’s best to remember Ben Franklin: “In this world, nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.”

The Security Blanket

Where does our need for certainty come from?

People with a high need for certainty are more prone to stereotypes than others and are less inclined to remember information that contradicts their stereotypes. They find ambiguity confusing and have a desire to plan out their lives rationally. First get a degree, a car, and then a career, find the most perfect partner, buy a home, and have beautiful babies. But then the economy breaks down, the job is lost, the partner has an affair with someone else, and one finds oneself packing boxes to move to a cheaper place. In an uncertain world, we cannot plan everything ahead. Here, we can only cross each bridge when we come to it, not beforehand. The very desire to plan and organize everything may be part of the problem, not the solution. There is a Yiddish joke: “Do you know how to make God laugh? Tell him your plans.”

To be sure, illusions have their function. Small children often need security blankets to soothe their fears. Yet for the mature adult, a high need for certainty can be a dangerous thing. It prevents us from learning to face the uncertainty pervading our lives. As hard as we try, we cannot make our lives risk-free the way we make our milk fat-free.

At the same time, a psychological need is not entirely to blame for the illusion of certainty. Manufacturers of certainty play a crucial role in cultivating the illusion. They delude us into thinking that our future is predictable, as long as the right technology is at hand.

Risk and Uncertainty

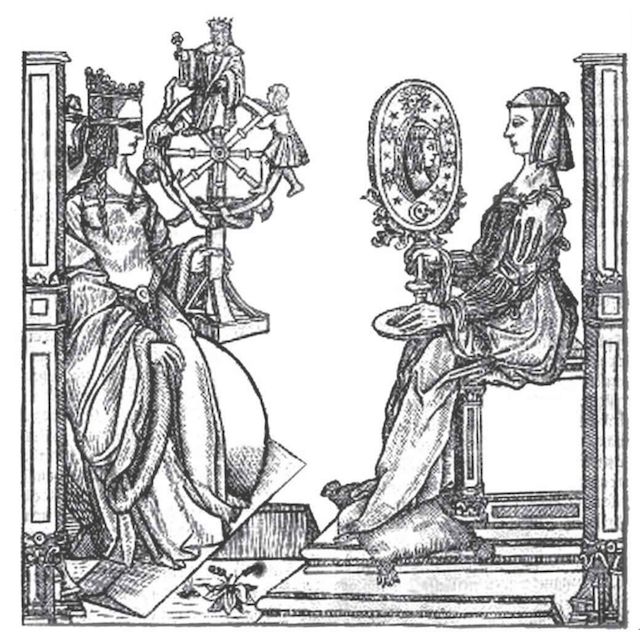

Two magnificently dressed young women sit upright on their chairs, calmly facing each other. Yet neither takes notice of the other. Fortuna, the fickle, wheel-toting goddess of chance, sits blindfolded on the left while human figures desperately climb, cling to, or tumble off the wheel in her hand. Sapientia, the calculating and vain deity of science, gazes into a hand-mirror, lost in admiration of herself. These two allegorical figures depict a long-standing polarity: Fortuna brings good or bad luck, depending on her mood, but science promises certainty.

This sixteenth-century woodcut was carved a century before one of the greatest revolutions in human thinking, the “probabilistic revolution,” colloquially known as the taming of chance. Its domestication began in the mid-seventeenth century. Since then, Fortuna’s opposition to Sapientia has evolved into an intimate relationship, not without attempts to snatch each other’s possessions. Science sought to liberate people from Fortuna’s wheel, to banish belief in fate, and replace chances with causes. Fortuna struck back by undermining science itself with chance and creating the vast empire of probability and statistics. After their struggles, neither remained the same: Fortuna was tamed, and science lost its certainty.

We explore more of the difference between risk and uncertainty, but the diagram above helps simplify things.

The value of heuristics

The twilight of uncertainty comes in different shades and degrees. Beginning in the seventeenth century, the probabilistic revolution gave humankind the skills of statistical thinking to triumph over Fortuna, but these skills were designed for the palest shade of uncertainty, a world of known risk, in short, risk. I use this term for a world where all alternatives, consequences, and probabilities are known. Lotteries and games of chance are examples. Most of the time, however, we live in a changing world where some of these are unknown: where we face unknown risks, or uncertainty. The world of uncertainty is huge compared to that of risk. … In an uncertain world, it is impossible to determine the optimal course of action by calculating the exact risks. We have to deal with “unknown unknowns.” Surprises happen. Even when calculation does not provide a clear answer, however, we have to make decisions. Thankfully we can do much better than frantically clinging to and tumbling off Fortuna’s wheel. Fortuna and Sapientia had a second brainchild alongside mathematical probability, which is often passed over: rules of thumb, known in scientific language as heuristics.

How decisions change based on risk/uncertainty

When making decisions, the two sets of mental tools are required:

1. RISK: If risks are known, good decisions require logic and statistical thinking.

2. UNCERTAINTY: If some risks are unknown, good decisions also require intuition and smart rules of thumb.

Most of the time we need a combination of the two.

***

Risk Savvy: How to Make Good Decisions is a great read throughout.